The ninth mile

On Flat Road, in Malvern Pennsylvania, at the far end of a half-mile long cornfield, nestled between the last ear and the local granite quarry, is the Union Hall graveyard. Surrounded by a four-foot stone wall, with one three-foot wide entryway, this small cemetery is the final resting place of several congregants of the first Amish meetinghouse settled in the United States, some of whom may have been laid to rest before the colonies declared their independence. With the exception of the section of wall that runs along Flat Road, the cemetery is engulfed by thick northeastern underbrush and briars. At night, especially in the dead of winter, it’s a creepy place.

Legend holds that a creature patrols the graveyard. It is a bastard, described best as a dog with a human head. Imagine the body of a rust colored pitbull, proudly carrying eight pounds of rugby ball-shaped evil on its shoulders, with one pound of face having been beaten into the head with a flail and mace. Those who witness the beast are known to die in the following 24 hours.

I’ve never see the monster, but I’d be lying if I said I don’t get a little nervous every time I drive by. I was introduced to the legend during the ninth mile of a ten mile run, as a high school freshman, as I ran by the cemetery for the first time. It was September 1976. My shaman was the senior captain of the cross country team.

I was thirteen. Rhetoric and hyperbole hadn’t been born yet.

Old School, New School

Our cross-country coach was old-school. He trained kamikazes; placing such a ruthless priority on mental toughness, self reliance and a commitment to the team that, if you were afraid to walk onto the school’s football field and punch an offensive lineman square in the face, you didn’t deserve a place on his team. The disparity between a 5' 10" distance runner and 6' 3" football player was a pock-marked wall for the weak to hide behind.

Rhetoric and hyperbole hadn’t been born yet.

Seasons bleed, cultures scream

Cross-country season bleeds almost seamlessly into winter track. Distance runners bleed less seamlessly, transitioning from the bucolic to the deafening and claustrophobic.

In the 1970s, in southeastern Pennsylvania, high school indoor track meets were held on Saturdays, in regional college field houses. Thirty tribes, each with forty athletes, jammed their culture, pride, fear, talent and volume into a shoe box.

Hollinger Field House

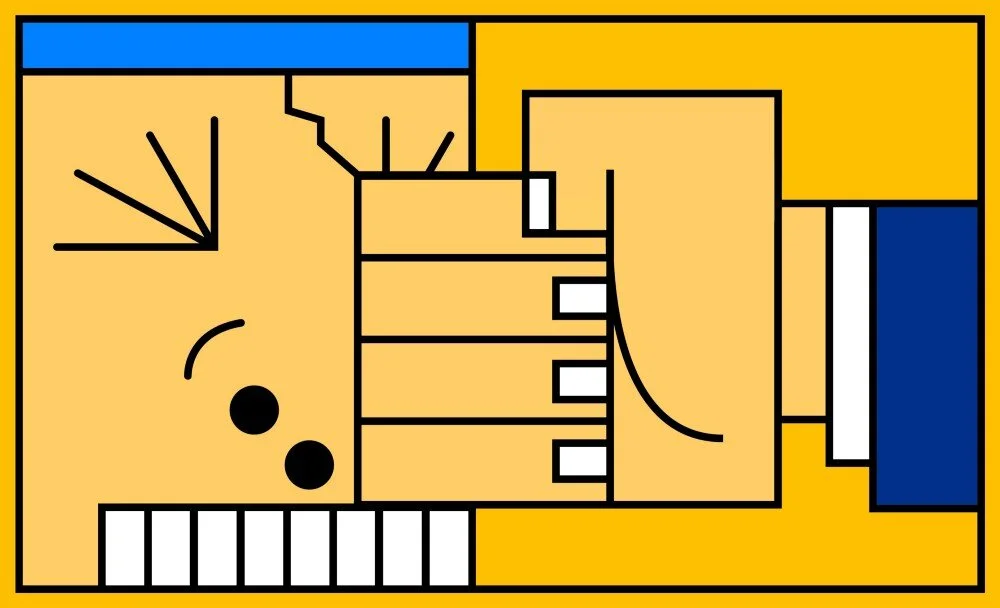

West Chester University owns a particularly weird field house. Like most college field houses, it is designed to serve many masters — basketball, wrestling, tennis, track & field. The architecture is odd. Almost an aircraft hangar, but extremely tight, with the building’s outside walls towering within eighteen inches of the outside lane of the three lane track. The edge of the basketball court, the building’s centerpiece, is inches inside the track’s first lane. The track, itself, is unusual — 146 yards. Twelve laps to the mile. From the center of the court to the apex of the roof, it is probably sixty feet. An open mouth waiting for a jet engine.

That jet engine is a high school winter track meet.

Getting jumped in

My shaman prepared me for another legend — a twelve-foot high, fifteen-foot wide, forty yards-long Thunderdome.

Every runner gets jumped in like a Crip, beaten and eaten whole, fighting for survival in the belly of a beast. Punches are thrown, elbows fly, teeth get knocked out. If I owned a pair of brass knuckles, the shaman recommended that I bring them. A switchblade would be good. A two-foot length of chain would be better. A flail and mace best.

I was terrified. The fate of those swallowed by the beast was left to my imagination.

The Beast

The most curious aspect of the Hollinger field house track is a tunnel that consumes an entire turn of the track — approximately 40 yards. Running underneath the grandstand, the sixty-foot ceiling drops down to fifteen. With the exception of the fifty yard dash, every track race enters the tunnel at least once. During a race, when a runner enters the tunnel, the jet engine convulses into silence. Leaving the tunnel, the engine sucks competitors back into its fan blades.

As a miler, I was scheduled to run through the tunnel twelve times. And, while I had plenty of opportunity to stand in discreet alcoves inside the tunnel during other races to watch virgins get jumped in, the choice never entered my mind. I waited.

Within thirty seconds of reacting to the starter’s gun, after being chewed up and spit out, I realized my shaman was an asshole.

Rhetoric and hyperbole had been born.

—